Why I Call Myself a “Facilitator of Development” (part 1)

“I didn’t want to leave them to deal with that energy on their own.” I didn’t exactly know what to make of Rutilio’s comment after our visit with the savings group leaders in San Juan Comalapa, Guatemala, but I knew on some level that my relationship to community development work had changed forever.

That year was my last year in Guatemala, after four years designing, implementing and handing over what is now the Community Finance Guatemala program (CFG) at GRACE Cares. CFG supports Indigenous Mayan women to improve their household financial management and create and manage their own community banks called savings groups (see hyperlink for details, this story is more philosophical than technical).

Over the course of those four years, my understanding of what it means to help others radically changed. To give you a sense of what I mean, when I first arrived in Nebaj, I was completely oblivious to the power dynamics at play as a white man from the U.S. in rural Guatemala telling Indigenous Mayan women that they should save more money. Even as I write that, I shake my head, mildly ashamed and bewildered by how naive I was (and at how powerful the dominant systems are that facilitated my oblivion.)

From there, I slowly discovered new perspectives on my role as a “development worker”. I learned about the popular international development idiom, “teach a man to fish” and started to see the many examples of good-intentioned, yet also potentially harmful, projects designed to “solve the communities problems”. I saw first hand how the dependency dynamic, created when governments or Non-Governmmental Organizations (NGO) opt for charity projects rather than capacity building, perpetuated the story that the community needed outside help in order to develop. And for a while, I out-right rejected those interventions as bad and problematic, unable to get past my black-and-white thinking.

Not wanting to be a part of the problem, but still believing that I had a role to play in supporting these communities, I grappled with this tension through trial and error. Many sparsely attended meetings, several failed attempts to get savings groups going, a Masters in Community Development from the University of New Hampshire, and 3 exciting and confusing years later I had somehow managed to help about 80 men and mostly women organize themselves into six savings groups. If I were to measure this result solely based on the ratio of hours worked to people supported, it would be hard to call it a success.

However, after having persevered for so long and learned so much, the stars did eventually align when I met Doña María, who would become the driving force propelling the CFG program to what it has become today.

You see, Doña María, an Indigenous Kaqchikel Maya woman from San Juan Comalapa, was well aware of the issues caused by government and NGO projects. She had been frustrated for years as the Coordinator of the women’s municipality office, watching countless groups of women only participate in projects that would give them something for free, such as a water filter, or a new stove. Any time she tried to offer educational workshops, without giving away something along with it, the attendance was sparse and she became increasingly disheartened.

At the time I met Doña Maria, I was beginning to change my approach to my work. I had discovered that once a group of women did decide to participate in the Community Finance program it had a big impact on their lives. I was no longer working out the kinks of the technical functions of a savings group or the curriculum of the financial literacy workshops, and was instead looking to train potential trainers of these groups.

Doña María was the perfect candidate because she was very well known in her community, respected as a leader, and seen as a source of positive changes in the lives of the families she worked with. To Doña María, I was also the perfect partner because, for better or for worse, a “gringo” from the U.S. was a big attraction in the more rural towns and lead to increases in attendance at meetings and workshops. Also, what I was offering was exactly what Doña María had been yearning for, a project designed to truly empower its recipients by helping them to discover the power they already had within them — a project that taught women how to take back control of their own lives.

Doña María quickly identified one of the leaders of the women’s groups she worked with, Adelina, as a prime candidate for her first group. Adelina had a fierce determination to serve her small “aldea” of Xiquin Sanai, born of years of hardship and forced resilience. She told me once:

“Life doesn’t need to be so hard for us here. We can make a better life for our families and our community. I don’t want others to have to go through what I have gone through.”

Sure enough, Adelina inspired 15 of her fellow community members to participate, and they have gone on to become the most successful savings group in the program to date — increasing in number and eventually inspiring many of their husbands and brothers to start a men’s group.

Doña María invited her son, Wilfred, to become a trainer along with her, as she only had a 6th-grade level of education and the more technical financial calculations, such as monthly loan payments, were just beyond her reach. Wilfred, however, was studying to become an engineer and thus math came naturally to him. The two of them became a dynamic duo going on to train 23 groups in three years (remember I trained 6 in the same amount of time?).

As my responsibilities shifted away from direct group training and more towards supporting this emerging local team it allowed me to spend more time thinking about the bigger picture strategy and to lean into the more philosophical underpinnings of both what we were trying to achieve, and my role in it all. I kept coming back to the question, how can I best be of service? And just like a good Japanese koan, the paradox presented to me through David Ellerman’s essay “Helping People to Help Themselves” was a catalyst for deepening my understanding.

“If development is seen basically as autonomous self-development, then there is a subtle paradox or conundrum in the whole notion of development assistance: how can an outside party (“helper”) assist those who are undertaking autonomous activities (the “doers”) without overriding or undercutting their autonomy?” -D. Ellerman

From there, so many more questions continued to arise:

- Yes, but what IS development?

- What does autonomous self-development even mean?

- Well, if my “help” is actually getting in the way then what’s the point?

- Where does “empowerment” enter into the mix?

- Am I just a vehicle for perpetuating the same dependency dynamics and neo-colonial, capitalist oppressive systems destroying us all???

- …and so many more (side note: what questions have you reckoned with in your work, dear reader?)

And then, at the risk of overusing an overused cliche, the stars aligned again! I woke up from a dream one morning and had all of the answers to all of my questions … no, not really, but I did discover a meta-framework that helped me to hold, and more effectively engage with, all of my questions. This meta-framework, or meta-theory, is called Integral Theory. In future stories I plan to dive into more detail about how I am using Integral in my life and work (and couldn’t stop if I tried), but for now I will give you the incredibly brief introduction.

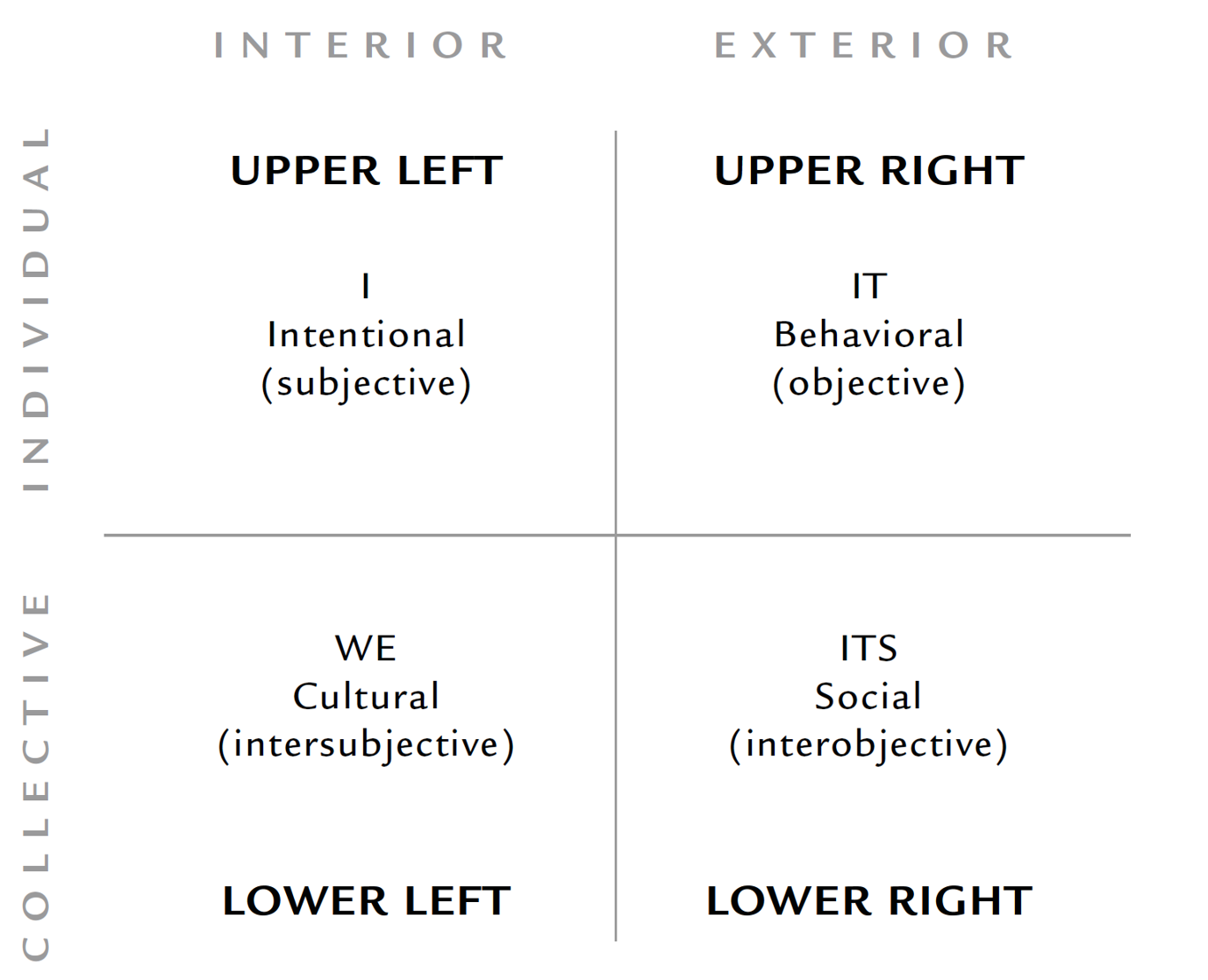

Basically, a genius philosopher, Ken Wilber pulled together all of the world’s wisdom into a comprehensive meta-framework commonly known as AQAL (short for All Quadrants, All Levels [and States, and Lines, and Types] that helps one understand and work with both the exterior and interior dimensions of reality at both the individual and collective levels. These “both/ands” are where the quadrants come from:

All four of these quadrants are present right here, right now. You as an individual reader are making sense in your mind of these words (Upper Left). The words are entering as light through your eyes (Upper Right). You and I are communicating and forming a relationship as I “speak” to you and you “understand” me (Lower Left). This is all made possible thanks to the internet, your computer/phone, the electricity, etc. (Lower Right).

It was through an online course I took with Integral Without Borders (IWB), while still in Guatemala, that I began to understand this mini-scenario I just described is happening, in some form or another, in each and every moment. For me, this new perspective on my experience was a huge “ah-ha!” and it led me to discover a new working definition of the term development:

Development is the moment by moment tetra-emergence of phenomena in all four quadrants as an expression of evolution itself.

As I continued to lean into this new understanding, my perspective on myself as a “development worker” changed. I started to see how I am not here to help develop communities with my knowledge and resources, as many NGOs are attempting to do . Nor am I a “helper” here to assist the “doers” in their own process of development, as Ellerman describes. Instead, I am both of those things and so much more.

I am an instrument of evolution itself and I have been gifted the opportunity to facilitate the evolutionary development of all the other instruments, myself included, along our paths toward greater and greater health and wholeness.

This description of who I am as someone who wants to help others is what I now call being a “facilitator of development”. And as tends to happen in life, my cognitive understanding of all of this came first before I truly “got it” experientially. It wasn’t until witnessing Gail Hochcachka, co-founder of IWB, and her good friends Rutilio, Walberto, Monique, and Larry from El Centro Bartolomé de las Casas in San Salvador facilitate a gathering in Guatemala that I started to understand at a deeper level what facilitation from an Integral consciousness actually means.

Stay tuned for part 2 to learn about that gathering and how understanding developmental theory can help us more effectively facilitate the development of ourselves and others.

Originally posted on Andrew's Medium Blog here: https://medium.com/@AndrUniverse